Sidestepping Risks From Job Loss After Age 50

When people in their 30s and 40s think about their earning trajectory through a normal retirement age, they should take into account the tendency for income growth to taper after age 40 in many fields, and the risks of unplanned early retirement, caused by health problems, corporate downsizing, or otherwise.

Job loss after age 40 (and particularly after age 50) presents heightened risks compared to those faced by younger workers. These risk factors were mentioned in a recent New York Times article discussing a research study by Connie Wanberg of the University of Minnesota and others. Intrigued by the NYT coverage, I read Wanberg’s study in full (you can too, here).

The study has tiny print and lots of statistics, but even so, a picture emerges that isn’t pretty.

Key findings include:

- Finding a replacement job is harder after age 50. In one study Wanberg cited of over 3,000 workers who lost jobs during 2011, 2012, and 2013, 67% had become reemployed by 2014. But – within the study group, only 58% of workers over age 50 were reemployed – compared to 72% of workers under age 50.

- Finding a job takes longer after age 50. The data set from that same study indicated that during any particular week of unemployment, each additional year of age lowered the odds of finding a job by 1.3%.

- After age 50, it’s harder to find a job with the same compensation. In the study data set, workers below age 30 who found jobs landed in positions paying (on average) 37% more, and replacement jobs for workers between ages 30 and 39 paid 7% more (on average). Workers over age 50, however, who found replacement jobs earned only 1% more on average.

The study tried to tease out the factors that make the job search landscape more difficult after age 50, and it focused on two main issues:

How does age correlate with changes in any particular person’s array of job skills and job-hunting resources? And, how does age determine exposure to environmental and cultural issues like changes in employment trends, technology, and employer stereotypes?

The study observed that compared to younger workers, older workers are less likely to be willing to relocate, which causes slower reemployment.

It also noted that social networks tend to shrink as workers age – reducing access to the informal job market and making it harder to match workers with opportunities.

Another issue Wanberg discussed very perceptively was how older workers are at heightened risk for skills obsolescence, given their tendency to have longer job tenures. Older workers also tend to have more “firm-specific capital” than younger workers – for instance, deep knowledge of one employer’s people, products, and history.

This capital is valuable to a particular firm, and tends to support higher compensation for older workers – but if the older workers are displaced, other employers tend not to value the former employer’s firm-specific capital, making it harder to find a replacement job and avoid a pay cut.

Older workers are more likely than younger workers to work in declining industries, often due to structural economic change since the time the older workers began their career. When these declining industries shed workers, more job seekers are competing for fewer job openings, which causes longer job searches and lower-quality replacement jobs for the affected workers.

Longer average job tenure for older workers often means a longer time has passed since they have searched for a job, which may leave the older workers unfamiliar with current job search tools, tactics, and interviewing norms. This can trigger a vicious cycle, if these workers feel more uncertainty and concern about the job search process, reducing the intensity and efficacy of their search efforts.

So, given this landscape, what can you do in the career management area to increase your odds for a quick and successful rebound if job loss affects you? I think the Wanberg study suggests several responses:

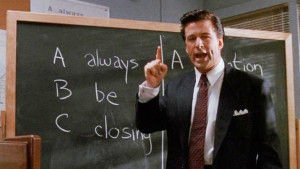

- Don’t stop networking. Even if your job doesn’t require you to “always be closing” and even if you don’t want to change jobs, you should “always be networking.” This doesn’t have to be endless rounds of business card swaps at the Chamber of Commerce, but it should be some way of intentionally nurturing meaningful relationships with people you find interesting, who are doing interesting things (and not just lunch every day with your three best friends in the offices down the hall).

- Cultivate new connections and maintain old ones before (ideally, years before) you might need them.

- If you work in a declining industry, think about the ones that are growing. Are they “adjacent” to your industry? Do they draw on skill sets similar to yours? Who do you know working in those growing industries? What can you do to improve relationships with those people?

- Avoid depreciation of your network by intentionally cultivating people younger than you.

- Take aggressive advantage of any tuition reimbursement or executive education opportunities your employer provides. If those opportunities aren’t employer-provided, go get them yourself.

The Wanberg study also has financial planning and estate planning implications:

- It may be wise to reconsider conventional advice about a six-month emergency fund. If you are highly compensated and in mid-career, or late-career, finding a replacement job will likely take (much) longer, so your emergency fund should be commensurately larger.

- If you’re under age 59 1/2 and don’t have access to capital outside a 401(k) or IRAs, your career problems can trigger income tax problems. Withdrawals from these plans will incur a 10% income tax penalty, and create income tax liability at the most unwelcome of times.

- You might consider permanent (cash value) life insurance as a very effective place to “park” the cash you might need if you face a mid-to-late career job loss, but don’t want to sit around idly in an era of near-zero yields on bank deposits. Cash value in many policies accrues tax-free dividends at rates comparable to those on high-yield bonds, yet is accessible within a few days through policy loans. These loans don’t affect your credit rating, and don’t require any credit checks. Receipt of the policy loan proceeds isn’t treated as taxable income, and there are no income tax penalties.

- If you don’t have enough wealth accrued yet to finance your own retirement, be cautious about funding (or overfunding) Section 529 plans. Loans are available for college, but not to cover lifestyle burn rate while you job search. As you get closer to a normal retirement date without an unwelcome career disruption, you can always help a young adult child repay those loans.

- Likewise, until you have your own retirement fully funded, be cautious about estate planning strategies that move wealth irretrievably outside your control. Spousal limited access trusts or completed gifts to self-settled asset protection trusts may be preferable to funding grantor retained annuity trusts or charitable remainder unitrusts.

Even as the post-2009 recovery ages, the U.S. economy still seems to be pretty resilient, and has shown considerable strength relative to the rest of the world. But as the recovery ages, so too are we. Don’t panic, but be mindful of how aging influences your job skills, options, and situations. Even when the pictures from your 20s have become dated from a fashion standpoint, keep developing your human capital, first, foremost, and always!