Managing Risk: Inheritance Strategies for the Upper Middle Class

Several months ago I read Cut Adrift: Families in Insecure Times by Marianne Cooper, a Stanford sociologist. Cooper’s chapters on the extremely professionally successful upper middle class and their project of “doing security” were particularly interesting.

These families were operating an increasingly unstable career and social environment, and devoted tremendous energy to enhancing their own financial security.

At the same time, parents also worried about launching their children on career and life pathways from which they could realistically hope to replicate their parents’ outcomes.

In the wake of the Great Recession and in a context of increasing global competition and winner-take-all income stratification, these concerns of Cooper’s upper middle class families seemed justified.

If the inheritance project of the Upper Class is managing abundance to enhance overall thriving of children and grandchildren, and the project of the Lower Upper Class is managing volatility in descendants’ upward or downward mobility outcomes, the project of the Upper Middle Class is managing risk.

Risk management is paramount for the Upper Middle Class because this class is still building wealth, but doesn’t yet have a capital base larger than what they might realistically need themselves.

Nonetheless, as life expectancy increases, children and grandchildren need to be launched in life when parents are still living.

More so than for their wealthier colleagues and relatives, Upper Middle Class wealth needs to be adroitly managed to hedge against several genuine risks. Some of the most significant are unplanned early retirement, a long term care event, or unexpected longevity.

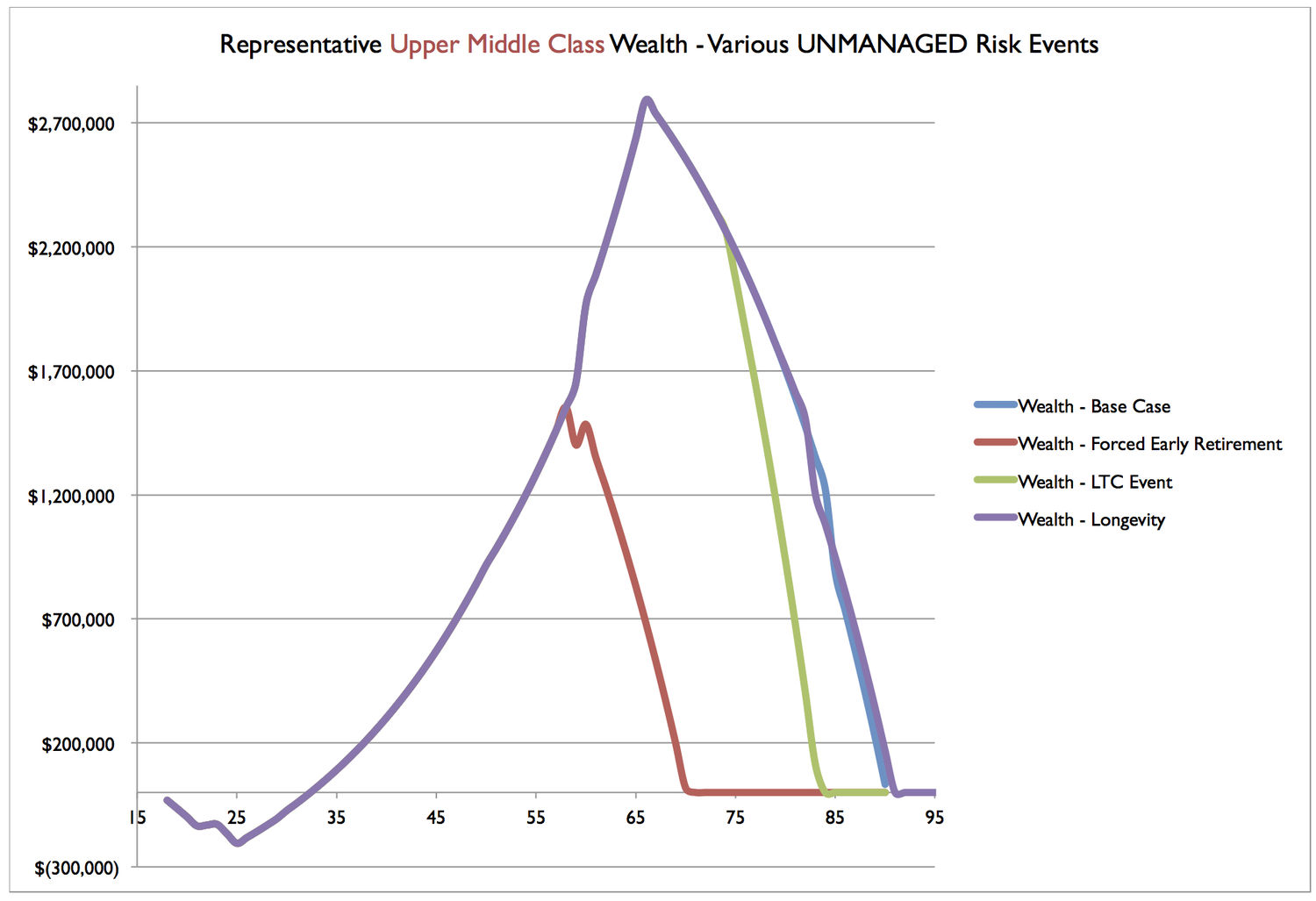

If any of these risk events occurs (let alone more than one), it can dramatically transform a family’s balance sheet for the worse. To explore these effects, I updated our inheritance model. Results of the model runs are summarized in the two charts below.

Each of the two model runs explored effects of three risks occurring in the life of Upper Middle Class Henry, the likable, hardworking mutual fund manager we’ve already met.

The unplanned early retirement risk event captures downsizing risk in corporate America (a risk many in Louisville have been thinking about recently with concern and compassion for friends at Humana).

For Henry, the model assumes he loses his job at age 58 when his mutual fund complex sells itself to a competitor, and Henry never works again at anywhere near the same professional level. To make ends meet, he taps his taxable savings, and starts drawing on his 401(k) after he turns 59 and 1/2.

In the long term care risk event, everything’s fine for Henry on the employment front, but when he’s 74, his wife, Claire, develops severe early-onset Alzheimer’s and lives in a nursing home for the next 9 years, at an uninsured cost of $120,000 per year. Claire dies when Henry’s 83, but he lives to age 90, doing his best to make things work with a much-reduced asset base.

In the unexpected longevity risk event, Henry lives to age 96. Because Henry retired on time at age 66, his asset base has to last 30 years, rather than 24. For Henry, this is a good problem to have, but it’s still a problem.

The first chart shows effects of these risk events on Upper Middle Class Henry if he makes no mid-course corrections.

If Henry suffers an unplanned early retirement, but doesn’t change his retirement spending of $190,000 per year, he’ll run out of assets right after reaching age 70. For the next 20 years, he’ll be living on Social Security income of about $25,000 per year.

If Henry suffers an unplanned early retirement, but doesn’t change his retirement spending of $190,000 per year, he’ll run out of assets right after reaching age 70. For the next 20 years, he’ll be living on Social Security income of about $25,000 per year.

If Henry doesn’t respond to Claire’s long term care event with any reductions in their other spending, his assets will be depleted shortly before age 74. For the next 15 years, he’ll be limited to the same $25,000 per year of Social Security.

If Henry’s longevity exceeds his expectations, his assets will be depleted at age 90, limiting him to Social Security income only for the next six years.

If, after enjoying a comfortable first phase of retirement, Henry rejoins the ranks of most American retirees who are limited to living on Social Security because they have virtually no financial assets, you might consider this a “High Class Problem.”

I bet that if you are Henry, it’s just a Big Problem, plain and simple, and that the abrupt adjustment would be scary and highly unwelcome.

Because Henry’s smart, what he’ll likely do if any of these risk events occur is reevaluate his situation and reduce his spending.

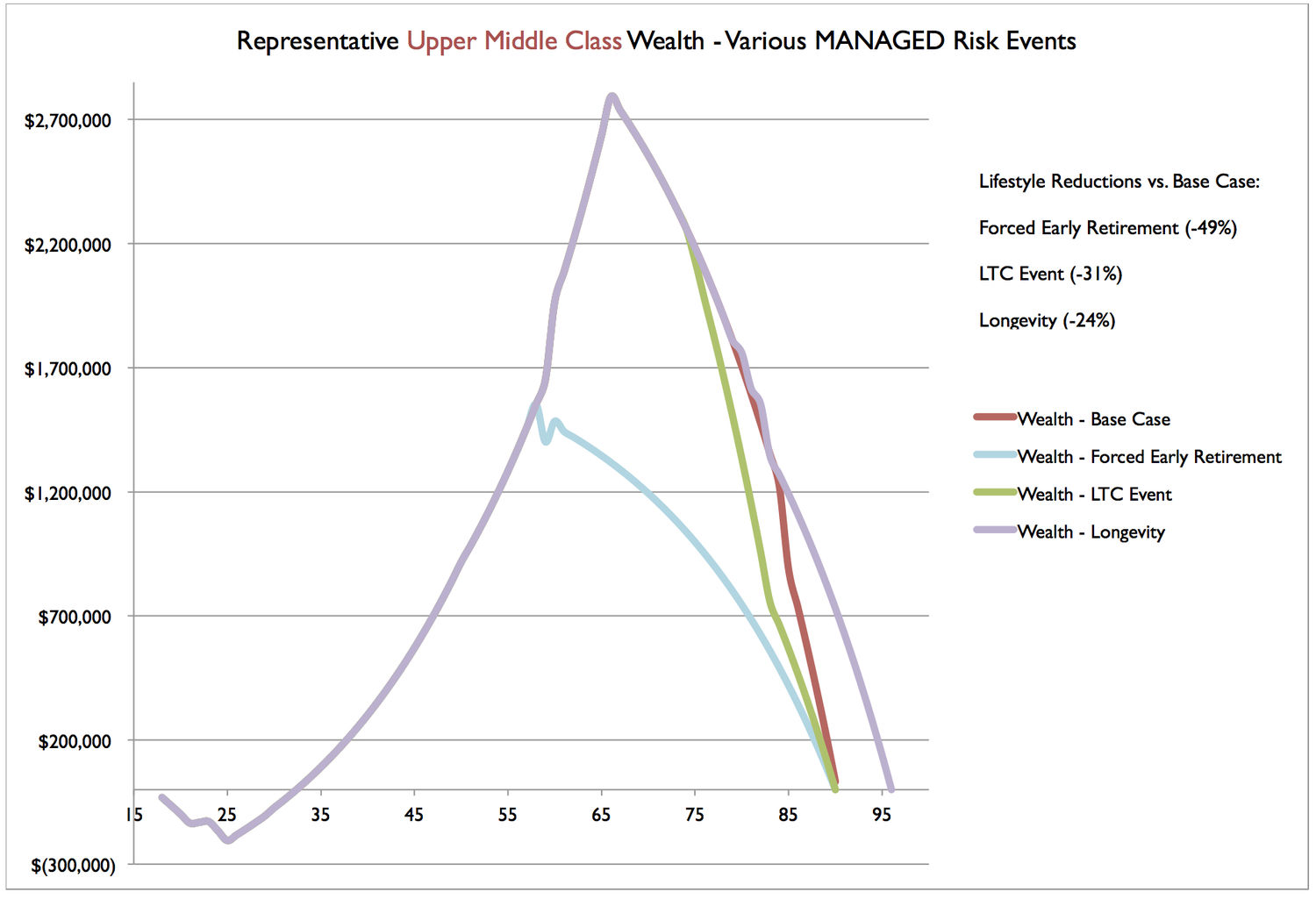

But by how much? The chart below summarizes his unpleasant options.

To make his funds last through unplanned early retirement, Henry has to reduce his spending by 49%, starting at age 60 once he realizes gainful reemployment isn’t going to happen.

After a long-term care event, he reduces non-LTC spending by 31%.

To manage longevity risk, at age 80, after one too many really positive annual checkups, he reduces his spending by 24% during the next decade.

Henry’s outcomes from reducing spending are better than those when he depletes all of his assets, but they have significant implications on what inheritance strategies make sense for his estate planning.

For Upper Middle Class Henry, deferring wealth transfers to his children until he’s as confident as possible he won’t need the funds himself is the only sensible option.

In Henry’s situation, income streams inheritance strategies that may work best in most Upper Class situations are truly unwise.

If a risk event occurs for Henry, the missing wealth reduces the amount of time until he runs out of assets, or compels even larger spending reductions.

Similarly, ad hoc gifts inheritance strategies that often work well for the Lower Upper Class are risky for Henry. If ad hoc gifts to children are modest in scale, and made in compelling circumstances, they may make sense.

But as Henry retains assets to hedge against his own risks, it’s unlikely he can (or from a standpoint of prudence, should) make similarly sized “matching” gifts at similar times to his other children.

So if Henry needs to make ad hoc gifts to one child, what should he do if he wants to be both prudent for himself, and fair to the others?

An answer more Upper Middle Class families should consider is inflation-adjusted equalization clauses in their estate plans.

For instance, Henry could keep track of gifts to each child from time to time.

Then, his estate plan could provide that these gifts would be inflation-adjusted to their current value at the time of his death. (This is easy to do with reference to CPI data published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.)

When Henry’s estate was distributed, children who had received less by gift could be “topped off” in inflation-adjusted dollars before the remainder of the estate was divided equally among children.

It’s not uncommon for adult children of elderly Upper Middle Class parents to have aged into very different financial circumstances as adults.

It’s natural for parents to want to help children of an under-earning child have opportunities for independent schooling, or to help bridge income shortfalls upon a child’s job loss, or avoid a “lifestyle crash” after a child’s divorce. But when the flow of funds from parents to children isn’t equal, resentments can build between siblings.

Sometimes, in the context of elderly parents, end of life healthcare issues, and estate administration, resentments over actual (or perceived) unfairness in gifting can boil over into litigation. Invariably, children who receive less claim that gifts were loans, while those who receive more claim that loans were gifts.

I believe the wisest inheritance strategy for Upper Middle Class parents to conserve resources they may need for themselves is deferral, along with keeping track of material ad hoc gifts when they do occur, with inflation-adjusted equalization clauses in estate plans to compensate for differences in amount and timing of ad hoc gifts among children.

This “deferral and equalization” approach may require a little more record keeping and a bit more planning effort.

Nonetheless, I think it’s the most realistic way to balance the financial life cycle needs of parents in an uncertain risk environment, while still making targeted investments to maximize opportunities (and minimize downward mobility risks) for children and grandchildren.