Red Ink Families in a Red Ink Nation

You never know what will happen when the mainstream press tries to cover estate planning. Sometimes, good intentions go astray. Other times, many column inches provide relatively little insight. Once in a while, something useful is shared with the general public. KYEstate$ isn’t sure what to make of this New York Times article from February 18: “Lending a Helping Hand, but With Restrictions”, and recommends that you click through, read the article, and decide for yourself.

KYEstate$ identifies four Big Themes in estate planning: 1) Family; 2) Money; 3) Taxes; and 4) the Family Business. The linked article features at least three of them – needy family members, money, and tax compliance/tax planning.

The article presents one key question: when family members need money, is it better to make a gift or a loan? It seems to hem, and haw, and not reach a strong conclusion either way. It is true that every inter-family borrowing situation is unique, and it’s wiser not to over-generalize. Nonetheless, in half a page, the article didn’t cover much new ground.

Let’s consider the gift vs. loan question ourselves…. Assuming that the donors or lenders (let’s call them parents) are able to transfer the funds (let’s assume to children) without jeopardizing their own financial security, here are some general approaches:

- If the child is using the parent as a substitute for a bank, use a loan, not a gift. (One example would be a down payment on a house.)

- If the child is asking for funds because of an acute need, especially one that is unforeseeable, consider a gift and not a loan. (Examples include a monthly stipend during a period of unemployment, or contribution to major medical bills.)

- For clients with taxable estates (or who expect to have taxable estates), and wish to make gifts larger than $13,000 per person per year, consider using a loan bearing interest at the AFR, which is usually lower than interest rates on the open market. If documented and administered properly, the loan will not be treated as a gift. More of the client’s estate tax and gift tax exemptions will remain available, and that’s a good thing.

The article didn’t discuss a third option: advancements. Advancements occur more often than they ought to. In the usual advancement situation, a child needs funds that they’re unlikely to ever be able to repay. The parent’s instincts, wise or unwise, are to provide the funds. The parent, laudably, wants to be fair to the other children who aren’t receiving funds. Therefore, some time after transferring the funds, the parent finally gets around to updating their estate plan to provide for the advancement. It can be difficult to draft the advancement with sufficient precision. For instance, how are family members going to reach agreement that the loans referenced in the updated estate plan are all of the loans that the parent made? How will they get comfortable that no other loans were made? Even if this issue is addressed, what about interest? If interest isn’t charged on the advancement, then is that result fair to the child(ren) to whom advancements weren’t made?

In many situations where the client or advisor’s first instinct is to meet the inter-family need for funds with an advancement, a loan documented with a promissory note may be a better option. The note can provide for interest-only payments at a generally low AFR, and a single balloon repayment of principal at a distant future date. The written promissory note makes it easier to track the amount owed, and to be confident no inter-family gifts/loans have been forgotten. When the parent/lender eventually passes away, the promissory note is distributed to the borrower/child as a part of the distribution the child would otherwise take from the parent’s estate, and the non-borrower siblings receive a proportionally larger fraction of non-promissory note assets.

The promissory note approach can present difficulties when the borrower/child owes more under the note than such child’s pro rata share of the parent/lender’s estate. The borrower/child will have to go “cash out of pocket” to repay the note. Sometimes that repayment won’t be feasible, for the same reason the borrower/child needed the funds in the first place.

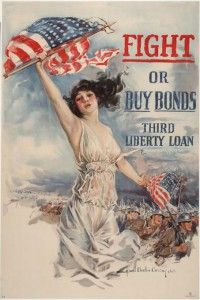

The NYT article dealt with inter-family borrowing, and that does present interesting issues for estate planners. Yet let’s not forget the real debtor-creditor relationship of our time: the U.S. and China. The average maturity of the Federal government’s debt is 48 months. Note: section 6166 offers better terms. Should we infer that decedents’ estates are more creditworthy than the U.S. government?

Let’s supplement the NYT‘s thoughts with some responses from KYEstate$ readers….

[polldaddy poll=2729029]