A Sherlock Holmes Approach to Your Income Statement

I think “budgets” are the reason many more people don’t have a sensible strategy for reaching their financial goals. The word “budget” creates obstacles in two ways.

I think “budgets” are the reason many more people don’t have a sensible strategy for reaching their financial goals. The word “budget” creates obstacles in two ways.

First, budgets imply choices, tradeoffs, and the unpleasant word “no.”

Second, most people lack even half the clarity about their spending that’s required to make a reasonably accurate budget. Without good data, the budget-building process bogs down and even when it moves ahead in fits and starts, results aren’t very useful.

In a perfect world, clients and their advisors would be able to immediately, effortlessly conjure up crisp, accurate, detailed data on inflows and outflows of cash, broken down into relevant categories.

We do not live in a perfect world.

But the cash flows question needs to be addressed, and done so in a way that isn’t a barrier to clients moving forward with planning.

First, let’s banish the “budget” word. This is not an exercise in encouraging spending reductions. But it should be an exercise in figuring out what your savings rate is, and what it could be, because your savings rate is one of the most powerful variables causing change in your Total Balance Sheet over time. To learn more about your actual and potential savings rate, you should consider your Total Income Statement.

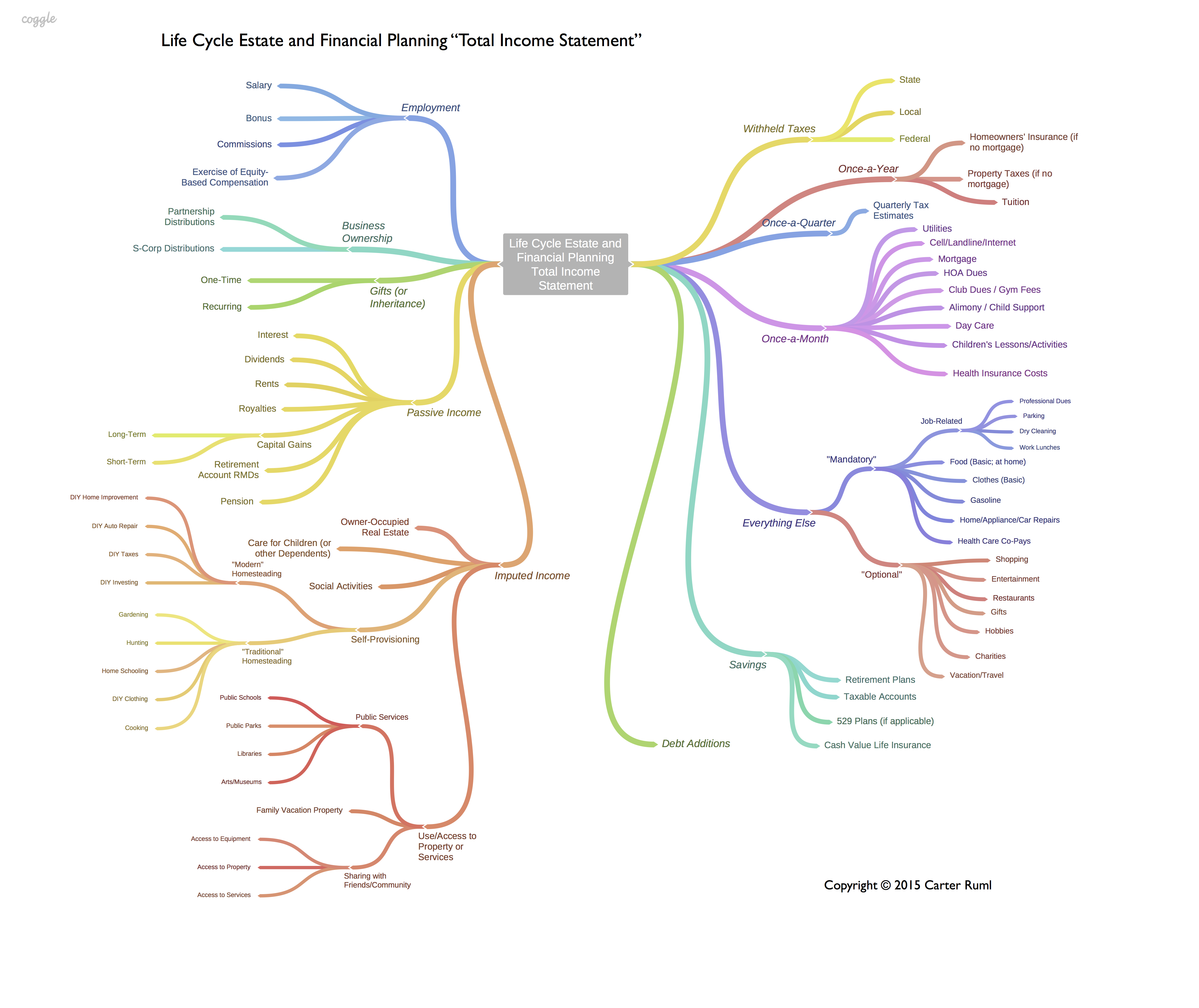

The Total Income Statement looks complicated, but it’s designed to be simple to use when applied with Holmesian deduction. As Sherlock said himself in The Sign of the Four:

The Total Income Statement looks complicated, but it’s designed to be simple to use when applied with Holmesian deduction. As Sherlock said himself in The Sign of the Four:

When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

The left side of the Total Income Statement is (unsurprisingly) your Income, which comes in the forms we think about often (employment, business ownership, and gifts or inheritance). You could consider these types of income your “Visible” income, an analogue to the Visible Assets discussed previously.

A more subtle form of income is your “Invisible” or “imputed” income, which is often produced by “Invisible” assets.

Imputed income is the value you receive from access to goods or services that you don’t have to pay for on the margin (at least in cash), and it can include the rent you don’t have to pay when you live in a house you own, access to a family vacation property, or the child care and household management services provided by a stay-at-home spouse.

A notable point about imputed income is that (generally) it’s not taxed.

Using public services such as public schools, museums, arts organizations, and parks can produce imputed income. Likewise, “self-provisioning” of goods and services you produce for yourself (rather than purchasing on the open market) produces imputed income. Self-provisioning can be traditional (such as gardening or home-schooling), or more “modern”, such as doing your own taxes, or managing your own investments.

All of your non-imputed income is generally rather easy to quantify. (Who hasn’t memorized their salary?) The parts of your income that aren’t top of mind are generally easy to confirm by obtaining year-end statements for investment accounts.

So much, then, for the inflows on your Total Income Statement. What about the Outflows, on the right side of the chart?

Some of these are easy to quantify, such as tax withholding (a math exercise that your accountant will find easy, even if you don’t find it fun).

I think in the real world clients tend to remember expenses incurred less frequently more easily than those they incur more frequently. For instance, annual expenses such as homeowners’ insurance, property taxes, and independent school or college tuition are generally top of mind. (If it’s something people grouse about at cocktail parties, it’s probably top of mind.)

Monthly expenses are usually not to hard to remember, or can be pulled up rather easily by consulting a recent credit card or bank statement. These monthly expenses include utilities, phone and internet bills, mortgage payments, health insurance costs, club dues, alimony and/or child support, day care costs, and children’s lessons or activities.

Generally, clients also have a good sense of what they’re “officially” saving – particularly regular contributions to retirement plans like 401(k)s, or regular contributions to taxable investment accounts, cash value life insurance premiums, and/or 529 plans for college funding.

Finally, people tend to know if (on average and over time) their bank balance is increasing, stable, or decreasing.

If it’s increasing, they tend to have a checking account that’s too large. If it’s stable, the checking account seems to bounce around a rather low, stable level, but there aren’t worries about checks clearing. If it’s decreasing, then debt must be increasing – whether on credit cards or home equity lines.

On the Outflows side of the Total Income Statement, the “only” category left is Everything Else.

Everything Else tends to come at irregular or sub-monthly intervals, and it’s very hard to forecast precisely. There are two varieties of Everything Else: mandatory, and optional. The mandatory subset includes non-discretionary food, clothing, gasoline, health care co-pays, and home and car repairs. The optional subset includes shopping, entertainment, restaurants, hobbies, charities, and vacation/travel.

Very few people know what they spend on Everything Else. With the Sherlock Holmes approach to your Total Income Statement, however, the good news is that you don’t have to know.

When you’re planning, you can back into the Everything Else number, because you know that your Income has to match your Outflows, including your savings (and/or increases to debt).

Once you note the annual and monthly expenses that are top of mind or easy to track down, and factor in your savings rate plus your debt additions, “whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth”.

What remains (and it may indeed seem improbable), must be the truth of what you’re spending on Everything Else.

And you won’t have had to tally the cost of a single latte or vacation….

You will have done it: solved the mystery of your own spending – even if it did take thirty minutes and a wireless Internet connection to pull a statement or two.

Figuring out spending is probably the hardest part of financial planning. Once it’s done, you can reap ongoing rewards in better quality planning that’s actually useful for improving your life.

Elementary? Maybe not quite, but we tried. And the results are well worth it.

Image above © BBC. Fair use rationale: critical discussion of their Sherlock television series. For detailed rationale, see here.